INTRODUCTION

In order to determine the nutrition and hydration needs of a basketball player, and develop plans to help meet those needs, the structure of game day, practices, and the off-season must be considered. The rules of the game, which allow for frequent substitutions, time-outs, breaks between quarters (high school and professional) and a halftime break, lend themselves to incorporating good nutrition and hydration habits. These habits should be developed and maintained in practices and training sessions throughout the year.

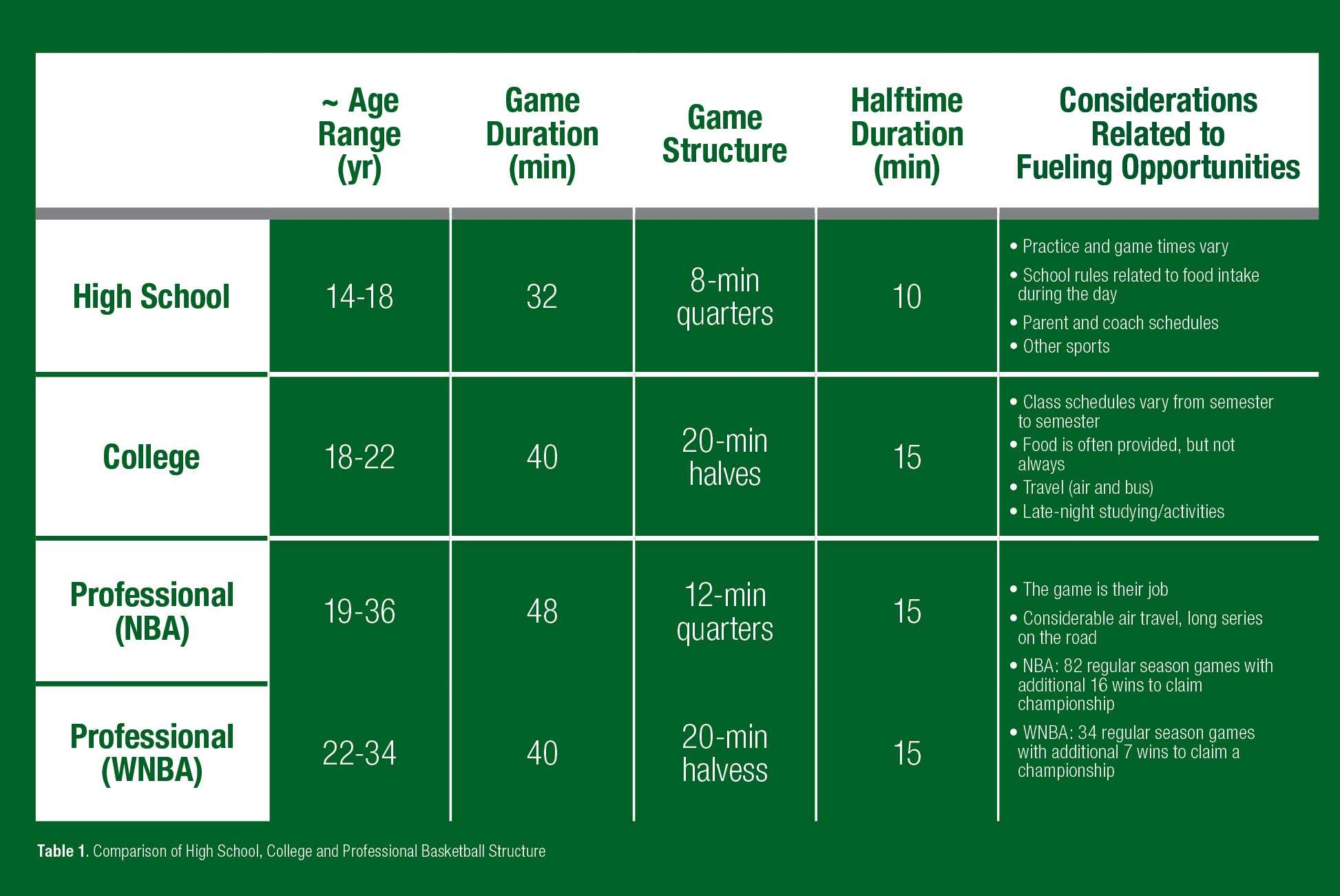

An actual game of basketball is of fairly short duration, ranging from 32-48 min of total playing time depending on the level. However, like any sport, players have responsibilities before and after a game, during which time nutrition and hydration should also be a consideration. During the season, practices will vary in duration and intensity, although most teams will practice, lift weights, prepare with film sessions, or compete six days per week. Basketball is a long season; for high school and college athletes it spans semesters and the holidays, which in many cases influences the nutrition and training of the athletes. Tournaments and playoffs provide unique challenges with multiple games in one day or games on consecutive days. Lastly, although off-season expectations vary based on the level, most basketball players are engaged and hydration plans should be developed within the structure of the game as well as with consideration for training and practices throughout the season and year-round.

PART I: HIGH SCHOOL

Alan Stein

Introduction

High school is a unique time period in working with athletes because of the wide range of age, maturity, and physical stature. Regardless of these differences, in general, many high school basketball players have poor nutritional habits, do not get sufficient sleep, and lack proper recovery and training techniques. Addressing these issues is vital to keeping players healthy and maximizing their performance.

The Competitive Season

High school basketball games usually occur 2–3 times per week and are structured as four 8-min quarters with a 10-min halftime. Most high schools will play 25–35 games per season, depending on tournament play. The structure of game day varies widely amongst high schools. Some may have a walk-through or shoot-around right after school on weekdays and in the morning of a weekend game. Coaches may have a set meal coordinated with a walk-through; others leave it up to the individual athletes and parents. During the warm-up, most coaches will take the team into the locker room at a set time, which can be used as a planned fueling opportunity. Because of the great variability in schedules and strategies of different coaches, as well as school rules on eating and drinking during the day, an individual approach needs to be used to ensure players are adequately fueled.

The frequency of practices during the season will vary depending on the game schedule, but are usually 4–5 times per week, approximately 2 hours in duration, and consist of moderate to high-intensity drills focused on skill work, conditioning, and offensive and defensive sets and schemes. The afternoon prior to most games, teams usually gather for 30–45 min to discuss the opponent’s scouting report, walk through plays, and get in additional shooting practice of low to moderate intensity. In addition, some coaches hold film sessions before practices 1–2 times per week, which require about 15–20 min of mental intensity. Most coaches will also maintain in-season strength workouts about 1–2 times per week, 20–30 min in duration, with moderate intensity. The timing of practices and workouts varies greatly, often due to gym availability and coaches’ schedules, since most don’t coach basketball full time. The player’s lunch schedule and school policies are another consideration. Therefore, high school players need help in determining not only the right foods to eat, but also the right time to eat in relation to their school day and practice/training/game schedules.

The Off-Season

The landscape of high school basketball in the United States has changed vastly over the past 20 years. For both males and females, the now year-round mental and physical demands of the sport are at an all-time high, as is the competition to earn a college scholarship. The two biggest changes include specializing in basketball at an earlier age and participation on AAU travel teams in addition to their high school team, thus making it a year-round sport. The structure of practices and training programs of high school basketball players should be adjusted accordingly to accommodate for these two trends. For example, players participating in the sport at this level of commitment could benefit from a year-round strength and conditioning program focused on injury prevention, using sound recovery techniques (including adequate sleep), and developing good nutrition and hydration habits.

PART II: COLLEGE BASKETBALL

Jeffery Stein, DPT, ATC

Introduction

Collegiate basketball athletes usually range in age from about 18–22 years. While physically and physiologically they are a more uniform group than a high school team, maturity levels vary greatly. The transition during the freshman year can be difficult for some as they move away from home for the first time. Transition challenges include establishing healthy eating and sleeping habits. Also during the freshman year, players are usually introduced to more intense collegiate strength and conditioning programs, and many players will greatly change their body composition over their collegiate careers.

Lastly, the student-athletes have class, practice, and eating schedules that vary each day and from semester to semester. Athletes must be able to juggle their academic schedules and the demands of their sport, as well as the social environment of a college campus. The day-to-day variability in schedules means preparation is important for proper fueling throughout the day.

The Competitive Season

College basketball games are structured with two 20–min halves with a 15–min halftime. Many colleges will play about 25–35 games per season, depending on the level (NCAA Division I, II, III, NAIA, or NJCAA) and tournament play. NCAA teams must follow the 20–hr rule, which states teams are allowed up to 20 hrs of team activities per week, not including competition. Team-related activities can include practice, film, and weight training. Most programs will practice 4–6 days per week, depending on the game schedule, and practices may be up to 3 h of high-intensity work. In addition to on-court time, athletes are expected to attend film sessions, strength train, and attend to injuries in the training room when needed. Overall, the time commitment is greater than as a high school athlete. The travel requirement during the competitive season is also greater and, depending on the level, more time-intensive. While the top Division I programs charter flights to return home the night after a game, smaller schools rely on bus trips and spend significant time on the road. The provision of food and nutrition services also varies based on level. Most top-level schools have a sports dietitian on staff for consultation and education, but even at the Division I level, the use of a registered dietician varies greatly between schools. At the majority of the major and mid-major universities, athletes are provided a “training table,” or a cafeteria with foods selected specifically for the athletes. However, per NCAA rules, only one meal at the training table can be provided per day while the athletes are on campus. Snacks, such as fruits, nuts, and bagels, can also be provided along with occasional meals on special occasions. At smaller schools, athletes rely on their own cafeteria plan, and the budget is often limited to provide meals and snacks on the road. Overall, the demands of the sport increase at the collegiate level compared to the HS and AAU levels, along with the increased demands placed on the athlete to also handle their academic, family, and social lives. The increased demands combined with the increased independence of the athlete make it difficult to ensure that they are appropriately fueling and getting enough rest.

The Off-Season

The majority of collegiate basketball players are one-sport athletes and dedicate the off-season to improving their game, although multi-sport athletes are found at every level of competition. Most collegiate basketball players will be given a short time off after the competitive season, usually 2–4 weeks, to recharge and catch up on family and school matters as necessary before starting back with skill work and strength and conditioning workouts.

Basketball commitments during the off-season will vary depending on the level and coaching demands. Spring semester workouts can range from captain-led workouts and open gyms to coach-led individual skill workouts that vary from 1 to 5 athletes at a time. The non-competitive season is also prime time for the strength and conditioning program to ramp up to work toward the specific goals set for each athlete. During the summer, athletes at smaller colleges are usually at home and often balance an off-season training program provided by their coach with a summer job. At larger schools, the athletes are usually on campus for summer school and summer workouts. These workouts include strength and conditioning sessions 3–5 days per week and on-court workouts with the coaches. Overall, during the off-season the NCAA allows up to 8 h of team-related activity per week, 2 h of which can be direct contact, with the basketball coaches on the court.

Back on campus in the fall, again the commitment will vary depending on the level. Most teams will start up with open gyms and strength and conditioning workouts as soon as the athletes arrive back on campus. Shortly after the start of the school year, individual workouts might take place with the coaching staffs. During the preseason, coaches can work with players on the court for up to 2 h per week, preparing for the competitive season.

PART III: PROFESSIONAL BASKETBALL

Jack Ransone, PhD, ATC

Introduction

The best of the best basketball players make it to the professional level. For the first time, the athlete’s schedule is completely dedicated to the sport; however, there are also increased demands for the athlete’s time for charity work, endorsements, social obligations, etc.

The Competitive Season

For male athletes in the United States, the National Basketball Association (NBA) regular season runs October-April, with the playoffs extending into June. It is not unusual to play 3 to 4 games per week with the possibility of competing on back-to-back days. Each team plays 8 preseason games and 82 games in the regular season. Teams competing in the World Championship finals will play over 100 games in a season and postseason. Women play in the Women’s National Basketball Association (WNBA), whose regular season of 34 games runs June—September, with playoffs extending into October. For both leagues, most team practices are short (less than 1 h) and infrequent due to game and travel demands. Travel requirements are extensive, including a minimum of 42 regular season games on the road for the NBA and 17 for the WNBA. Both the NBA and WNBA have the luxury of traveling by charter airplane and staying at the best 5-star hotels with excellent restaurants. Many teams also employ or consult with a sports dietitian. However, nutrition is still a challenge, as most players seek meals on their own at restaurants outside the control of the team. Additionally, during a game, hydration is always a challenge. Inadequate hydration during competition can be further compromised by the demand for air travel immediately post game (low humidity environment of the fuselage) for half of the regular season games. Given the length of the regular season, frequency of games, and travel demands, proper nutrition and hydration practices are important and should be planned into the schedule wherever possible.

The Off-Season

Professional athletes are employed based on their ability to stay competitive. Therefore, the off-season is a period of time to recover from the long season, rehab injuries, develop a base fitness level, and focus on skill development. Overall the schedule is very individual. For example, younger NBA players might play in the summer league, while veterans may focus more on recovery and some specific skill work. All players will participate in training camp and preseason games, essentially extending the competitive season.